Gale D.Moore

These documents were sent to the Museum Archives by Carol Woodruff, daughter of Gale D.Moore.

Gale D.Moore

THE TELEGRAM

In my mind my Dad was a great man. He worked hard to keep my mother, sister and me, warm, dry and never hungry. That in itself was no little feat during the depression years. He was generous, honest to a fault, made friends easily had a great sense of humor. But he didn’t trust airplanes. Neither airplanes, nor snakes , nor for that matter democrats were on his list of things to be held in high regard. One of his favorite stories was about the fellow that went to the judge to get his name changed from “Franklin Delano Puke to “John “Puke”.

The family left Illinois and ended up in California in mid 1940. Less than two years later and a few months after Pearl Harbor I had my 18th birthday and became eligible for the draft. A year to the day later I was inducted into The Army of the United States of America. This turn of events did not cause my Dad any unusual degree of apprehension beyond what any parent felt when one of their own was potentially about to be placed in harms way.

After graduation from High School I new that induction into some branch of the service was just a matter of time so while biding my time I took an interim job working as a civilian for the Army Air Force (AAF) in Sacramento. This being early in the war McClelland Field was just tooling up for the long haul and didn’t have much work that needed to be done. I was pretty unhappy spending my time trying to look busy, when I thought there were important things that I needed to be done and that should be helping with the doing. Needless to say I was not the least bit enthused in the way the AAF was doing business.

So when I was inducted and went through all the exams, evaluations and interviews I expressly requested that I not be assigned to the AAF. As all of us who were in the service soon found out, you most probably got exactly the opposite of what you asked for. I hadn’t been around long enough to acquire that bit of information at that time but in about a month I got my first lesson and found myself on a train bound for the Army Air Force Radio Training School in Sioux Falls South Dakota.

Now all of this didn’t bother my dad too much because radio training schools weren’t noted for their excessive use of airplanes and there were a lot of radios on the ground. He became a little uneasy when I went to Arial Gunners school in Laredo, TX and even less relaxed when I was transferred to March Field and subjected to the foibles of the B24 Liberator for the next few months while getting to know all I could about that weapon of war. He lived in the general area of March Field then so we got to sit and talk a few times before I transferred on. He didn’t say too much about my chosen way to help dispose of the enemies of democracy which was what WWII was all about but it was apparent that he didn’t think God had intended man to fly and would have been just as happy if I had decided to keep one foot on the ground.

Eventually Uncle Sam entrusted a brand spanking new B24 H to the care of me and the rest of the crew and we set off to see what destiny had in store for us. We flew from Hamilton Field, CA to Morrison Field, Fl in about four days and departed from the zone of the interior three days later, April 27, 1944. We open our sealed orders while in the air and learned we were headed for the 8AAF in England. Of all the crews that had trained with us at March Field only two headed east. All the others went to the South Pacific. We went to England and the other crew that was with us when we left the States had orders to India. Have no idea what happened to any of them.

Ten hours after take off we arrived on the Island of Trinidad. Three days later we had hopped from base to base and ended up in Fortaleza, on the east coast of Brazil from which we were to embark on our flight across the South Atlantic to Africa. However the pilot had developed laryngitis and we were delayed three days. Left Fortaleza May 3 and after 12 hours and 1946 miles of night flying we landed in Dakar and the pilot went back into the hospital. The powers that be then decided we should be moved on so they found a pilot to ferry the remainder of the crew and our brand new pilotless airplane to Marrekech, Morrocco. While we waited there for our beloved pilot to get well and join us, a couple of planes came through that needed parts that were not available in the local inventory so that part was “borrowed” from our means of transportation.. After a few days of cannibalization we no longer had a flyable aircraft but it was again decided to send the enlisted men along to Casablanca, this time via the Air Transport Command (ATC).

We hung around that area of the world for a few more days and were eventually joined by the healthy officers and finally by the recuperated pilot. We still had no airplane to call our own so the ATC was again called upon and we arrived someplace in the Lands End area of England in the middle of the night of June 3, 1944 some 37 days after we left the States. Not really a speed run. No one ever accused us of rushing into combat. Took me less than a third of that time to come home by ship after all the foolishness on my part was completed.

After completing a couple of weeks of training in Northern Ireland on the way things were done on that side of the Atlantic, we eventually arrived at our assigned destination the 493Bomb Group.

Now back in those days security was rated pretty high so I couldn’t tell anyone where I was, where I was going or why they had not heard from me for awhile which didn‘t give anyone at home a warm fuzzy feeling of contentment. After we got to the bomb group I still couldn‘t say much except that I had finally arrived where I was supposed to be and they would hopefully be hearing from me on a more regular basis. All this really told them was that those damn airplanes hadn’t taken their toll of me yet, at least up to the time the latest letter was written. Flew my first mission July 6,1944 and my 35th and last on Christmas Day of ’44.

Guess I had not really thought through how much this not knowing was taking its toll on the folks back home but now I could tell them that the combat was over. We didn’t have e-mail or cell phones then or even access to whatever international phone service there was in those days so I figured a telegram was the answer. That is what I did. The next morning I went trapzing down to the telegraph office about three feet of the ground the most of the way, so happy and proud that I was still alive, and sent a telegram to my wife letting her in on the good news. My wife Alice lived in Whittier Ca. with my parents while I was overseas. She was working and not at home when the wire arrived but my dad worked the graveyard shift and was home. Telegrams from overseas during a war connotes bad news. Evidently my dad thought the worst. He did not open the telegram since it was not addressed to him but immediately got on the bus and made the trip to down town LA where Alice was working. She said he walked into the building as white as a sheet, walked up to the counter and handed her the envelope. She probably wasn’t too calm at this point either but opened it read it told my dad, “He is OK”. She said he never uttered a sound all the while he was there but turned around, walked out of the building and went home..

My dad lived to the age of 93. He still disliked snakes and had never voted for a democrat. He did fly a few times commercially in later life but like his only son, never was completely comfortable in or around airplanes. He never mentioned the telegram to me.

BRIEFING NOTES – 493RD

CALIFORNIA TO COMBAT

(Or half way around the world)

IN EIGHTY-ONE DAYS

About 6AM on Monday, April 17, 1944 I kissed my wife goodbye, and about 2PM crawled into a brand spanking new B-24 at Hamilton Field in Northern California and headed out to whatever our destination was to be. Later we found out that Debach, England was that destination. We ended up that night in Kingman, Arizona; one of only two crews out of our whole group that trained at March Field that didn’t go to the Pacific. We and the other crew stayed pretty much together until we left the states. Our orders were to the ETO, theirs’ to the CBI. There but for the Grace of God . . . . Got a little cross ways with the nose gunner that first day out. He threw up in the bomb bay shortly before landing and refused to clean it up. Some poor flight line guy must have come to the rescue because the next morning we took off for Amarillo, Texas in our airplane which one again looked and smelled brand new. Way the hell out over northern New Mexico someplace the pilot let his hair down a little which we found out later was out of character for him. We dropped down so we were just buzzing the coyotes and cacti and Johnson, the co-pilot played “I’ll Walk Alone” on his trumpet over the command radio, SCR 275.

Arrived Amarillo on April 18, stayed around a couple of days waiting on the weather and then on to Abilene. Went to the PX for breakfast and had the biggest steak I ever saw, before or since. It hung over the platter all the way around. Still being a growing boy at the time, I was able to do what my mother always told me, “Eat everything on your plate.”

On the following day, April 23, we left for Drysberg, Tennessee. We all went to the Enlisted Men’s Club that evening. I never was much of a drinker nor had been around people that were drinkers. I discovered something that bothered me for years. The guys around me were getting loaded, but I was doing great. The only thing was I couldn’t talk without slurring my words. And me being perfectly sober too.

Monday, April 24 we took off for Morrison Field, FL and arrived about 4PM. I grew up in Illinois so I thought I was no stranger to high humidity, but I hadn’t seen anything yet. When I went to bed at night I took off my “sun tans” and folded them up as best I could on a footlocker. The next morning they felt and looked like they had been dipped in water.

Left Morrison Field Thursday, April 27 about 10:30PM and started our overseas adventure. The hop to Walter Field Trinidad was about 1900 miles and took all night. Landed mid morning, sans the trailing wire antenna that I had forgotten to retract.

Although I don’t remember some 65 years later, but my notes say we were billeted in a two story barracks with open sides. Wonder how that worked? I do remember that the natives were very dark complexioned and about as mean and dower and untrustworthy looking as this 20 year old had ever seen.

We left Walter Field about 4AM the next day, Saturday, April 29, 1944 for Belem, Brazil and made it the same day. This time my notes say we were in one-story accommodations, which were pretty sad, as was the chow.

Took off for Fortaleza, Brazil the following morning, Sunday, April 30 about 6AM and landed about 3PM that afternoon. This was to be our jumping off place for the flight to Africa. That adventure was to be delayed a couple more days by an occurrence that was to become commonplace. Bob Trimble, the pilot went into the hospital for some sort of respiratory problem, which was to plague him for some little while.

The Air Base at Fortaleza was very nice. I thought the chow was better than in the states. Slept in tents with good beds and cement floors. Had natives to sweep up and roll down the sides of the tents every time a rainstorm came upon the scene, which seemed to happen every few minutes. Don’t know where those guys came from, but they always arrived soon enough to avoid letting us get wet. Getting this kind of attention may have been old hat to you officers, but we enlisted men weren’t used to it.

This was the first time since we left Hamilton Field that we had time to go into town. Either the 2nd or 3rd day after we got there we took a look at downtown Fortaleza. Rode in town on a charcoal powered taxi. Wasn’t very powerful, but we went full bore right down the middle of the road with pedestrians and carts and donkeys just getting out of the way.

We came upon a building that was open on the sidewalk side and housed a number of young ladies. I think this was a barracks type accommodation where these girls lived, ate, and conducted business. None of us was very anxious to get involved, but there was a lot of good-natured chatter back and forth with a couple of the gals. However, one of the young ladies was particularly impressed that the stone in the ring she was wearing matched the blue in the flight officer’s bars. Won’t identify which, but one of our flight officers agreed that this coincidence was significant enough not to be ignored so he disappeared with her to discuss the situation further, I presume.

Johnson, the co-pilot, kept tract of Trimble’s condition and reported back to us. Our mid day report indicated that he would be in the hospital another night at least and so no one made any preparations for an all night flight, like storing up a little sleep. However, a little after 6PM we got the word that Trimble had just been released from the hospital and we would fly the South Atlantic that night. Sure enough about 10PM on Wednesday, May 3, 1944 instead of heading for the sack for a good night’s sleep, we climbed into that B24 and headed out across the South Atlantic for Dakar, French Equatorial Africa.

There were a lot of planes in the air that night. Our B24 had the range to make the 1946 mile 12 hour trip non-stop. Those with lesser range made a refueling stop at Ascension Island. To keep track of all these planes, a ground station CW radio queried each plane at periodic intervals. If that plane was pretty much in position, a new report was sent. If nothing was heard from the plane it was assumed that the plane was in trouble.

The tropics are a continual parade of electrical storms, each a source of radio static. I sat there at that radio for twelve hours with the gain cranked way up and listened to short periods of severe static followed by long periods where nothing was intelligible. However, I persevered and each time we were queried I replied but never could determine whether my transmissions were received. With all the static and no sleep for over 24 hours I was not sure I did a very good job of it. But since no one came out when we landed to tell us that they thought we were lost, I guess I got through once in a while. I’ve spent a lot of time since then with earphones plugged in my ears but never anything like that.

I had nothing but respect for Vischuck after that flight. Left to his own devices he brought us in right over the end of the runway about noon May 5th.

Dakar wasn’t much to look at. The camp was poor, hot and covered with red dust. Natives extremely black and had a very rank odor. We slept on cots in dirty tents with gravel floors and bug netting.

Trimble went back into the hospital there and so began another delay. There wasn’t much to occupy our time so one day as we walked around the base we came on a reasonable looking building that had a vacant room with a table and chairs. So we went in and started playing cards. Shortly after we got settled someone stuck his nose in quickly and disappeared. Almost immediately this bird colonel, Col. Keen came barging in fuming and inquired what we thought we, 6 enlisted men, were doing in the Officers Club. Then he chewed on me for not standing at attention when he came into the room. Quote: Sergeant Do you always sit on your fat ass when being addressed by a full colonel? Unquote.

I’m not sure we realized we were in the Officers Club, but we found out in no uncertain terms. That was Col. Keen and we were supposedly arrested and restricted to our bunks for the remainder of our stay in Dakar. Even after we finally got to Debach, I half expected the MP’s to descend and cart me off to my more deserved punishment. And sometimes after a particularly rough mission I hoped they would.

The base ran GI trucks to the ocean every so often and since we couldn’t play cards anymore and regardless of our “convict status” we spent most of the time at the beach in the afternoon or at the movies in the evening.

Ten days later, May 15, Trimble was still in the hospital so we left Dakar about 7 AM with a Captain Van Eden at the helm. We flew almost straight north over the Sahara to Marrakech, Morocco, arrived about 3PM. Van Eden parked our brand new B24 and disappeared. We never saw him again and we never flew that plane again. We were destined to stay in Marrakech another 10 days and by that time our plane was being cannibalized for parts needed for planes that had a pilot. It was missing a hydraulic accumulator and two engines when we left. I doubt if it ever flew again let alone made it to England.

It was pretty hot over the desert at the low altitude we were flying so Joe decided to remove one of the waist windows to get a little breeze. He wasn’t then and still isn’t a big man, probably 135 pounds sopping wet, so when he loosened the window the suction on the window tried to suck him and the window out into the slip stream. When his feet got about 6 inches off the floor, Joe decided that going out that window in the middle of the Sahara especially without a parachute wasn’t really a very good thing to have happen so he let go. Wonder if that waist window became a picture window in some Bedouin’s tent?

One of the other crews moving through Dakar had a little white American Eskimo pup that they fed beer out of a canteen cup. Rumor had it that the English were real sticklers for keeping animals out of England so they took off without the dog. That didn’t set to good with us, especially George, so we decided to take the little dog with us and try to smuggle him under his coat while the rest of us were cleared. We had that little dog around the barracks in Debach for awhile but the poor little thing contacted distemper and died shortly after we got there. We had named him “Flack”. Since the war my wife and I have had an “American Eskimo” around the house one at a time for more than thirty years. Maybe the love affair started with “Flack” that little dog we appropriated in Dakar.

Anyway with the waist window gone we had to keep pretty close tabs on “Flack” because he made a couple of attempts to jump out. If it wasn’t a good idea for Joe to take a header into the Sahara, it probably wasn’t a good idea for that dog either.

Marrakech turned out to be a fairly nice French resort town. Stayed there in a tent with wooden floors and screen sides. Slept on cots. Went to town quite frequently from 1 to 6PM. Large Medina or native section that was off limits to us. Very good chow. Nice USO. Sold candy and cigarettes to native, and my only dabble in the black market.

We the enlisted men, left Marrakech on Thursday, May 25 about 5PM on a C47, loaded with a whole bunch of foreign ground officers. Air was very rough and these officers were throwing up all over the place while we American enlisted men sat there and looked bored. Actually we were smirking.

Arrived in Casablanca about 7PM. Slept in tents with dirt floors. We had put most of our bags in a warehouse someplace. Good thing too as water flowed through the tents from the rain that first night. Had to change tent sites 3 times while we were there before we got the water problem solved. Joe, George, and Johnson joined us 2 days later since that C47 didn’t have room for us all. Trimble showed up on the scene again a few days later.

Casablanca was the best town we had seen since we left the states. The French inhabitants were a little cool to us. Think a lot of them had their sympathies with the Germans who occupied the town before they were run off by the Americans and the Brits. At least that is what a young clerk told me in a shop I stopped in one day. Spoke very good English, better than I. She asked me about something and I told her it was hard to do. She didn’t understand hard but knew difficult. From then on we referred to a certain condition as “having a difficult on”.

Speaking of that, as soon as the plane stopped rolling at each new field, Chico would gather his endless supply of Hershey bars and silk stockings and disappear till much later. Could not understand how he knew how to get off the base and which direction to go, but apparently he did almost as soon as the wheels stopped rolling. He never got caught and never suffered the consequences health wise as far as I know. Many years later we had a Tom cat that would disappear all night and lay around all day with an exhausted but satisfied look and a stupid grin on his face. I called him Chico.

Left Casablanca Friday, June 2 about 8PM via C87 for an 8 hour airtime flight to England. A C87 is a B24 configured as a transport. Flew sort of NW out over the Atlantic then north till we were even with England and then swung back east. All this to stay far off the German occupied French coast. This also accounted for the night flight.

Arrived in Nequay, England about 6AM Saturday, June 3 1944. Foggy. Ate chow and boarded a train about 11 for Stone. Road all day that Saturday and arrived in Stone about 1AM Sunday, June 4. Foggy. Had nice quarters, four to a room. Did KP while there.

About 10AM on June 6, 1944 someone stuck his head into the barracks and announced that we had just invaded the continent of Europe. This was D-Day. To this day I can’t understand how we could have flown into the area and rode around on a train without seeing some of the preparations that were going on. If we hadn’t taken to so long to fly from the states to England, some 48 days since we started out from Hamilton Field, we would probably have participated in the invasion. Another example of the luck of the draw, or fate or a guardian angel.

Friday, June 9. Left Stone about 8AM. Arrived in Warington by train. Left there by B24 (C87) about 1PM and crossed the Irish Sea. Arrived Clunto, Northern Ireland about 4PM. Started 10 days of school Monday, June 12. Intelligence and radio school. The officers and I stayed there. Others went to Greencastle for gunnery. Had a first sergeant that had been in the army 30 years.

Even back then there was a lot of tension between the Catholic and Protestants. A couple of times the permanent party woke us and ran us outside in the middle of the night. We stood around while they played soldier protecting us. All this under the guise of repelling a potential German invasion over the border from Ireland into Northern Ireland or a German parachute landing. Both of these seemed pretty far-fetched since Northern Ireland is a long way from German occupied territory and I was sure the Germans had more productive ways of conducting a war than trying to occupy an Army training facility. We were admonished to leave no guns or ammunition in the barracks. Don’t remember what we did with our 45s when we were in school, at chow, or making use of the latrine facilities.

Thursday, June 22. Left Clunto by train to Belfast. Boarded a boat there & met the rest of the crew. Left there about 7PM and crossed the Irish Sea in the boat. Arrived Friday, June 23 about 8PM. Assigned to 863rd Sq. Went to school for 3 and ½ days. Flew some training missions to practice what we learned in Northern Ireland and familiarize ourselves with the lay of the land.

The barracks of the EM’s were assigned to was vacant when we moved in except for one staff sergeant. It turned out the barracks housed two crews. One was on a mission when we arrived and the other, his had been shot down a few days previously when they flew without him while he was temporarily grounded. He and they had competed three missions. He did that same thing twice more, i.e. three crews, three missions with each and lost the crew when he got grounded and he did not fly the 4th mission with them. Three crews a total of 9 missions. He decided that was enough and had himself taken off of flying status. Saw him only one time after that over near the flight line issuing cushions, “biscuits” that the Brits used 3 of in lieu of a mattress. Seemed happy, lost one stripe but he was alive.

The other crew assigned to our barracks returned from their mission that afternoon. A couple of months later they were shot down. Think they all were taken POW and eventually made it home.

The 493rd Bomb Group (Heavy) was the last heavy bomb group constituted in the 8th Army Air Force. The original members trained as a group in McCook, Nebraska. They left there on May 2, 1944 and left the continental U.S. from an airfield in New Hampshire on May 10. They flew the northern route to the UK. They arrived in Wales on May 14, arrived at Debach shortly thereafter, went through all their familiarization training and on June 6, 1944, D-Day, the group flew its first combat mission.

We on the other had left Hamilton Field April 17, 1944 about 2 weeks before the boys from McCook and were directed to fly the southern route to England because it was still too cold up North. We left Morrison Field, Florida April 27, 1944 still about 2 weeks ahead but didn’t arrive in the UK until June 3, 1944 and didn’t fly our first mission until July 6th, one month later. Took them 5 days to make the trip whereas it took us 36. It took them some 36 days to get into combat after leaving the US shores where as we made it in a lightning fast 71, 81 since we left Hamilton.

I completed my 35th and last mission on Christmas Day, 1944 without receiving a scratch or getting shot up very bad. Flew “routine missions” to targets that just a few days earlier or later were holly hell. Had ice that formed on the wings break off just as we cleared the end of the runway. Regardless of how many scary and life threatening the situations they all tended to come out OK without much help from me. Became somewhat of a fatalist as a result. Still I often wonder what fate would have had in store had we gone to the Pacific or the CBI or flown the northern route or if Trimble had stayed out of sickbay. Thank you, God. As wars go, I had a good one.

Gale Moore

The Crew:

Bob Trimble pilot, deceased; Warren Johnson, co-pilot, deceased; Walt Vischuk, navigator, deceased; Ray Joseph, bombardier; Joe Sarina, engineer; Gale Moore, radio; Al Stafford, waist; Chico Mendez, nose (after 6 missions transferred to Italy), deceased; Grady Hendricks, ball, deceased; George DiEso, tail, deceased.

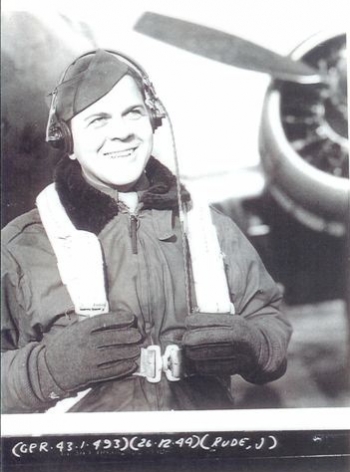

Jack Rude

We had the sad news that our great friend and former veteran Jack Rude passed away.

Our condolences and sympathy go out to Jack's family and friends in America.

Our condolences and sympathy go out to Jack's family and friends in America.

Notes taken when Jack Rude talked to John Lovell (Archivist for the 493rd BG).

Jack enlisted in 1942 at the age of 18. He was a tail gunner on a B17 and he joined Bud Harris' crew. He has made 19 visits back to Debach since the time he served here.

Below are his memories of the living conditions at Debach.

“Living conditions during the winter of 44/45 were very harsh. The nissen huts were not insulated, rough concrete floors, nearly always covered in mud, only one small stove and only one bucket of coke was the daily ration. Usually three enlisted crews, (non commissioned, 15 or 16 men) in each hut. Officers lived on the same site but on the other side of the road. Two tier bunks were the normal with no locker facilities for storing uniforms or personal items. Everything on the floor, always damp and mice enjoyed this haven. The crews who were not on a mission collected the fuel for the stove, but by the time the mission crew returned, it was all gone. Anything that could burn was stolen. To be in bed was the only place to try and keep warm. As the ablution blocks were freezing, no hot water, it was not unheard of to go to London on a 48 hour pass and spend most of the time in the bath - if you could arrange enough coins to keep the meter going.

Keeping the same clothes on ‘day and night’ for 14 days was about the ‘social limit’. Best uniforms were cleaned in ‘gasolene’ so travelling in a train was dangerous if anyone smoked!

Life for flyers was tough on both counts – stay in bed or fly missions. An English winter is not ideal, living in a damp hut or being shot at in the sky at 26,000 ft is no option.

Ed Borowy

S/Sgt Ed J Borowy, born in Chicago, flew 21 missions and was awarded the Air Medal with two oak leaf clusters. He was a ball turret gunner in both B24s and B17s.

After completing his initial training in the U.S. with the Lt Albert L Tucker crew, Ed came over to the U.K. on the Queen Elizabeth and eventually arrived in Debach on the 6th June 1944, where the crew commenced their familiarisation training and flew several practice missions before proceeding to enemy territory. 1 month after arriving, the Tucker crew flew their first mission, on 7th July 1944, to France and then went on to fly 2 further missions together. However, in late July 1944 the ball turrets were removed from the B-24s and Ed reluctantly left the crew and was detailed to work in the armoury, cleaning and preparing the guns. He continued to be billeted with the enlisted men of his original crew and also the men from 2 other crews he had trained with. When the 493rd BG changed over to flying B-17s, Ed remained in the armoury and a “new” ball turret gunner was assigned to the Tucker crew.

On 12th September, the crew was shot down on the raid over Magdeburg and all but one of the men were killed (the radio operator, Floyd Ford Jr, was made a P.O.W.). To make matters worse the other crew who shared the Nissen hut with Ed was also lost.

Ed told us “That night sleeping, or rather lying awake, was his loneliest night in the Army”. The next morning he requested to be returned to flying duty and joined the Lt Edward Glotfelty crew, as ball turret gunner and went on to fly a further 18 missions.

When the Edward Glotfelty crew finished their 35th and final mission on 24th December 1944, Ed had only completed 21 missions. Wondering what he would do now he approached his Pilot, who assured him he was part of the crew and would be going home with them. By some means, Ed was able to stay with his new crew on the journey to Southampton and sailed home to America with them on the SS Uruguay on 30th January 1945

Below is a copy of an email sent to us by Ed Borowy

To the Taylors You asked me how I was able to run across some of these strange items. Well for one thing I was always a pack rat so it came easy to hang onto anything that I happened to accumulate. Will tell you a tale on how I came across the Hitler’s mother’s medal that is now resting in your museum. The second item is a 25 cal. Mauser Automatic german revolver and the third item is a small copper medal in the shape of the country of France and engraved on it is the year 1944 with the French cross and also engraved is the words – welcome liberators. Now we go on to how I came in possession of said items.

I was one of many crews that flew out of the 493rd at Debach. Our trail started in Muroc, California where we trained as a bomb group that were supposed to go to England as a complete bomb group. But due to the timing we were all split up and became replacement crews.

The trip to England was on the Queen Elizabeth landing in Scotland on the morning of D-Day. Then being herded onto a whistle tooting English train found our way down to Debach where we were told that we were the first replacement crews to come to the 493rd.

Now we became just one of the many who were there to just try to get our missions in and with a lot of luck make it back home. Well, my stars must have been lined up correctly as on Christmas Eve 1944 I flew my last mission. As anyone in the Army knows things do not happen over nite and it was about two weeks later, we received our shipping orders to go to our embarkation point to leave for home from Southampton docks. Arriving there to our dismay we were no longer heroes with privileges of just lying around – we soon found our names on several work details. Mine happened to be, eventually, to my benefit. It was a guard duty post in a building that had all the barracks bags and B-4 that would wind up in the ships hold. It was on my midnight to 4.00am shift that I heard a knock at the door. Opening it there stood the most bedraggled soldier that I’ve seen in my life. Asking him whats up – this poor soul started to explain that he had just returned from the Battle of the Bulge and he had nothing but the miserable clothes on his back and asked if I could help him. Coming from Chicago, it did not bother me to bend the rules a little – so I invited him in and closed the door. We commenced looking through the B-4 bags and of course the officers had the best underwear so that was number one. Then finding a Corporal bag we fitted him with a shirt, pants and blouse. Shoes were a little harder to find but eventually this was also taken care of. Even found some candy and cookies. Now before me stood a happy soldier. He then told me he would like to return the favor and that is when he gave me the Hitler’s Mother’s Medal … the German Mouser automatic and the French medal. Was a little hesitant smuggling the Mouser home but made it OK… So now you know the complete story. Hope you have enjoyed it.

Love Stef and Ed.

The 'Hitler's Mothers Medal' can be viewed in "Veteran's Corner" within the Nissen Hut Museum.

A TRIP TO DEBACH

Over the past few years my children have encouraged me to make a trip back to the air field that took me on 28 missions on a B-24 named Baby Doll and a B-17 named Baby Doll II. My son had made a trip to Debach in 1997 and brought back pictures of a sad dilapidated control tower and overgrown air field. In 2000, me and my son made a European trip stopping at Debach to spend a little time taking photos and witnessing first hand the crumbling control tower. Again, in 2004, Clay and I made a second trip to Europe, but did not get a chance to visit Debach as we were on our way to Normandie, France for the 60th reunion of D-Day. My daughter, Nancy has made several trips to Europe, but never had the chance to stop at Debach. In 2009, we discussed a trip, but plans never developed. This year Nancy did not give up, she felt that it was important that we make a trip to Debach. On June 4th we (Clay, Nancy and I) left for London on our way to the 66th D-Day reunion and open house at Debach. Nancy had e-mailed Prilly Taylor that we would be there for the celebration. However, our e-mails were lost in cyberspace and Nancy did not receive Prilly’s response---offering to meet us in Ipswich.

We arrived in London on June 5th planning to go to the farm for the dance that night; however Clay became ill we were unable to go. When Prilly did not received a response to her e-mail and we did not show up at the dance, they assumed that we did not make the trip. When we arrived at the farm on June 6th you can’t imagine the surprise---both for us and for the Taylor’s. We were greeted like Royalty and everyone was so excited that we made the trip. That morning was foggy, cool, with a fine mist of rain in the air, perfect English weather to greet a 493rd veteran back to his air base. We were assigned a special host/guide for the day, a Mr. Brian Ward. Brian was 16 years old during WWII and spent considerable time at the 493rd . He was a local kid who loved airplanes and the 493rd “adopted” him and he even managed to find his way onto a B17 and received 6 or 7 rides. He has remained loyal to the 493rd and works tirelessly on all the projects and feels as close to this airfield as any airman who served there. We were awestruck at the renovation that have been made and I could hardly recognize the control tower and all that has been done to transform it into a wonderful museum honoring the men of the 493rd. There were several 100 people in attendance that day—all there to honor the young Americans that flew from their countryside. The people of Debach and the surrounding countryside have a great attachment to this airfield and feel very strongly that is a vital part of their heritage and sense of community. They spoke openly of the gratitude they feel toward the American airmen who sacrificed their life and limb to fight against the Nazi death grip. Most of those in attendance were not even born until well after WWII had ended and had no first hand experience of this airfield, but this has no effect on their loyalty and commitment to preserve and maintain this history. These people give a whole new meaning to the word Volunteerism. They have given 100’s of hours of their time, energy and resources to see that these buildings are renovated and are even building new structures to resemble those that were standing during wartime. All this is being done without 1 cent of Government money, grants, or any subsidy; they are doing this with personal funds so as to maintain 100% control over all decisions as to how this living memorial shall be utilized. School children still make fieldtrips to the farm and spent the day learning of the 493rd and all the accomplishments of the “Mighty Eighth”. There are plans to construct as many buildings as possible that will bring this airfield closer to her original appearance. The perimeter road is still there, as is part of the main runway. The road from the control tower to the main air strip is still there as well. The parachute building still stands as does the Norden bombsight hut. We were greeted with some very special entertainment—a local gent owns a P-51 and he buzzed the airfield for at least 10 minutes----what memories returned when I heard the engine produce that high pitch whine when he made a sharp banking turn---it was a special treat to a perfect day to see this war bird again.

Prilly is working hard to develop the museum and hopes that she can secure memorabilia to make the museum more “personal” to the 493rd. She has extended a wish to all 493rd veterans; to have pictures of crews, pictures of daily life at the base, and memorabilia that can be generously shared for permanent display within the museum.

Richard, Prilly, Brian and all the people of Debach were the perfect hosts for this most special day. Their single focus is on the veterans and on this day, their focus was on me and my family who had made this most personal pilgrimage. I stood on top of the control tower with my children and looked out on the run way where 66 years ago on that day, I flew my first mission. If possible, make this trip and take with you someone to share the memories-------- there are still plenty to experience.

William “Bill” Toombs

861st SQ.

Flight Engineer May-Oct1944